Looking for Life on Mars – Issue 107: The Edge

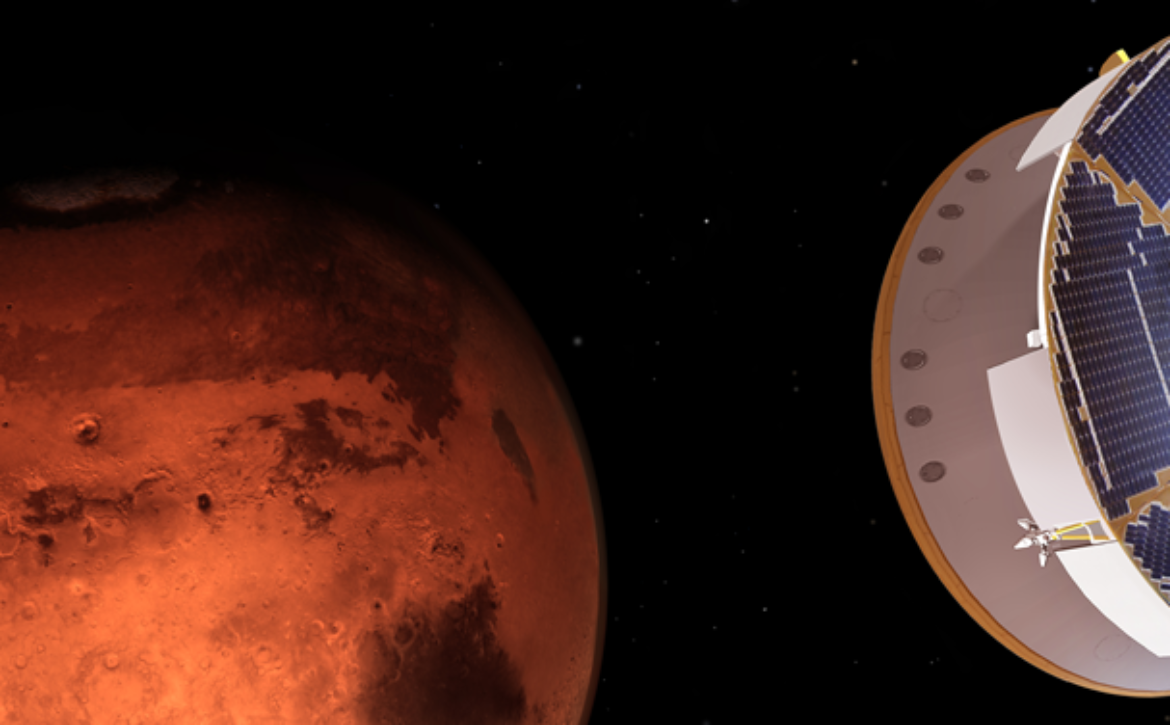

Terri Randall’s hope when he makes films about space exploration—like Chasing Pluto, for example, or Death Dive to Saturn—is that viewers share scientists’ excitement. That rush of success and discovery. “Look at this moment, and look at his eyes, and look at what he’s so excited to do, and work on for so many years, and take so many risks to answer big questions,” Randall says. “That’s what I hope happens when people watch the film, that they get some of that.”Randall’s latest try at immersing his audience in that experience is the PBS/NOVA documentary Looking for Life on Mars, which was nominated for best long-form film in the “Science in Nature” category at the 2021 Jackson Wild film festival. He followed the scientists and engineers who, during a pandemic, managed to build, launch, and land Perseverance, an SUV-sized, plutonium-powered rover on the Red Planet’s surface. The aim is to carry out a wealth of scientific explorations and technical experiments to lay the groundwork for actually returning pieces of Mars to Earth in the future.Everything I learnt made me feel more connected to Mars as a real place that possibly in the past was quite different. Caleb Scharf, the director of astrobiology at Columbia University, caught up with the filmmaker (and writer, director, and producer) to hear how Randall thought about creating this latest film—as well as his upcoming one, on the launch of the James Webb Telescope, in December 2021. It was an interesting role reversal: Scharf is the sort of scientist Randall usually interviews himself. The astrobiologist was keen to understand the filmmaker’s perspective, beginning with how Randall decided to distill the complexity of the mission to Mars into a compelling story.Building and placing a robotic roving science laboratory on Mars is an outrageous ambition. There are thousands of people involved. The stakes are incredibly high. What was your process for creating a narrative out of all of it?Well, especially with this mission, it’s really difficult because it’s not just landing and, like with the Curiosity rover, getting reports from time to time on what the rover is discovering. In this case, it’s the rover, a helicopter, it’s MOXIE (an experiment to produce oxygen from the martian atmosphere), it’s the European Space Agency’s involvement, it’s the retrieval of samples 10 years from now—an extraordinarily mind-blowing process. It was hard to figure out what to hone in on. But there are a few major points to the mission. The biggest one is landing in Jezero crater, into an area where NASA has never landed a rover before, to search for evidence that life may have existed on Mars. Everything revolves around that.One of the things that really struck me about the film is how you don’t shy away from the technical details. There are incredibly convoluted and complicated steps in this kind of planetary exploration. How did you decide how far to take us into the weeds?It’s always a balance. I’m always thinking of what I would understand as a person who doesn’t have a science background. I was a painter in college, so I don’t have the science background. I kind of know what the audience feels like without a science background. And then I figure out what I would want to know, what I find interesting, but then also figure out how to balance that with what the scientists will feel is adequate. Because scientists want to explain things in-depth, and I understand why, but their in-depth explanation can lose the rest of us. But I also don’t want my truncated explanation to become inaccurate. That’s part of the trick, to figure out how much you need to tell of a specific story.Even the concept of lift for the helicopter (Ingenuity). We went through so many phases of speaking to experts to try to figure out how to show this. I mean, you could do a whole film on lift. So how much to include to give the audience some information, but also keep the story moving forward. Some of the simplest-sounding concepts are, as you know, really hard to explain. I rely a lot on my own sensibility. When I’m in the editing room, if I’m watching something over and over again, and I still find it interesting and I follow the story, that tells me that I’m going to hold the audience as they’re learning this content.I just find the science is so inspirational. People trying to answer these big questions, like where did we come from? How did this all begin? Scientists tend to put caveats in everything we say: “It’s probably, it’s maybe, it’s perhaps, it’s like this.” We use metaphors and analogies.Well, sometimes scientists can be extremely excited about telling you something, and I’ll find out later that I don’t understand what they’re talking about. And I will go back and listen, and listen, and then maybe finally figure out what they were talking about, and then figure out how I can explain what I’ve learned. I also understand it’s important for scientists to be accurate, and to always let the audience know: This is what we understand so far. I also find it’s really interesting that scientists get so excited about learning they were wrong, because that means they’ve found something new.Right now I’m actually working on a film about the James Webb Space Telescope. When I ask the scientists, “What are you most excited about?” they’re always like, “What? I don’t know. The question I didn’t think of asking.” That’s always an interesting aspect of interviewing scientists.Your films bring that excitement, that seat-of-your-pants element to this, which is present in almost any form of space exploration. I think perhaps people can forget that.When we were finishing Looking for Life on Mars, and waiting for the footage to come in of the rover landing, nobody was really sure because that footage had never been attempted before. There were off-the-shelf HD cameras on the outside of the rover in several locations. Nobody was really sure what they were going to get.We knew we were going to be on the air Wednesday and the footage was going to be shown to the public on Monday. It was coming in over the weekend and I was talking to Ian Clark, a systems engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)—he couldn’t tell me because it wasn’t released yet, but he was hinting that we were going to like what we were going to see. I said, “Okay.” And that footage was just spectacular. It’s surreal.I was struck how the COVID-19 pandemic provides this fascinating tension in your film. A reminder of all the obstacles for humans doing any kind of extremely ambitious and difficult thing. I was wondering what your experience was, making a film in a pandemic.At the beginning, I just wasn’t really sure. Well, nobody at that point was really sure exactly how we were going to do production. The number one concern is that you don’t want anybody to get sick. We could not get onto JPL property at all until the rover landing. We weren’t permitted to interview JPL personnel indoors. Luckily it was California, so we had relatively good weather.What was really wonderful, is that the scientists who were so busy dealing with the pandemic, and getting this immensely complicated project off the ground, were happy to take the time to share their work with great enthusiasm. I really admired their tenacity and their commitment to the project, during impossible circumstances for people to work in, and to still pull it off so beautifully.How did you manage all of the interviews you had to do?I did a lot of interviews over Zoom with a crew on site. Whenever I could, I would do the interviews in person, and try to create scenes that I could shoot during a pandemic. For the MOXIE story, working with Mike Hecht, we were talking about the amount of fuel that a rocket would need to launch from Mars, compared to how much fuel an ordinary truck takes. We came up with the idea that we can film that outside. I can put a GoPro in his truck. I can have the cameraman in the back, wired, so we could get decent sound, and we could do our outdoor interviews and we could create scenes. It was kind of amazing that it all worked out.This is the fifth film I’ve done on space exploration, and each one of these films for NOVA focuses on a major event in the mission. I covered the Pluto flyby and the end of the Cassini mission. During those events we were on site, I was picking up scenes for the excitement of the end. Then putting it on the air within, in some cases, hours.For several key events for this Mars mission the team couldn’t even be together, right?Right. At the end of the film, team members couldn’t themselves be on-site at JPL. We put GoPros in the homes of some of the team members, and it gave a different perspective, because they’re alone, and they’re experiencing this, and they’re just sharing their thoughts in a way that you wouldn’t normally see. It did in a way create opportunities to see how the team rallies, and moves forward despite the obstacles. I loved the plaque that they put (on the mission) for the healthcare workers. I mean, what a beautiful touch.It’s really interesting that scientists get so excited about learning they were wrong, because that means they’ve found something new. You make use of a lot of computer-generated imagery and visualization tools. NASA itself uses these. Those tools are amazing. We can render scenes that we in person can’t participate in. As a documentary filmmaker that gives you all sorts of opportunities for storytelling. But do you ever feel that something about the grit and noise of reality gets lost?I think that we actually have to be careful. At NOVA, with the executive producers, we’ll discuss what is said at the bottom of the screen to make sure people understand something’s not real. But the thing about working on a film about space exploration is that you can’t shoot on location! So, you are limited by animation, but then there’s also a lot of great imagery.And that’s also why we try to come up with good analogies that aren’t necessarily animation. That’s always fun and very challenging. I remember when I was working on our Pluto film, trying to describe a gravity assist, and there’s a lot of animation of it. But we ended up with a rollerblading team where they did the whip, because that was a really interesting down-to-earth visual example of that gravity push. Took a long time to come up with the whip, and get enough scientists to agree that it worked.No matter how much we might talk about Mars in casual conversation, there’s no getting away from the fact that it’s another world that has a very different history than the Earth. Does Mars now seem more or less alien to you?It feels far less alien. Before, I hadn’t looked at the amount of imagery we have of Mars. There’s so much beautiful material. You could look at these pictures forever, they’re just so gorgeous. It’s very Earth-like, as some of the scientists in the film described. You can see pictures of Mars that remind you of Earth. So, for me, it made it much more real. And the fact that Jezero Crater is an area that was once an ancient lake, and then visualizing that lake. Everything I learnt made me feel more connected to Mars as a real place that possibly in the past was quite different.With your film on the James Webb Space Telescope, due to launch December 2021, you’re now reaching much farther out into the universe.Talk about big, talk about risky, talk about the payoff. I mean, as a scientist, I’m wondering from your perspective really what you hope to find out. Which is probably everything.Well, my biggest hope is that it all works! As we sit here a few months before launch—and then it’ll be another, I believe, four to six months before the first images, or first data, really arrive—much like almost everyone in astronomy and perhaps the rest of science, my hope is that it all takes place. But at what stage are you in that documentary? Are you currently filming? Are you constructing the story?Constructing the story, and we’re going to start filming in November. Launch was just announced as December 18, so we have to figure out the production schedule based on the moving launch. And, with every one of these films, we never know at the time we start, when NOVA green-lights a project like this, if something will happen that will change the story dramatically.What if the Pluto flyby came back with no images, what do you do then? What if something unfortunate happens with the Rover landing on Mars? On these projects we’ll make like 95 percent of the film. Leave the last five minutes or so empty to be filled in during the event. And if something should really go wrong, then we have to think about what we say at that point. How do we explain how something like this happens, and what have we learnt from the process?You must feel some of the butterflies, the adrenaline, the tension.Oh, absolutely. I mean, that’s one of the things that’s wonderful about working on these films. With every single one of them, it’s like I’m there with the team. I’ve gotten to know some of the team members. They’ve gotten to know me as well, and I’m getting the opportunity to share in this amazing experience. Like with the first Pluto flyby when the pictures came in, hundreds of people went crazy with joy.Let me ask a final question about making Looking for Life on Mars. What had the most impact on you personally, as you made this particular film. Was it the science? Was it the people? Was it the relief of getting it done in the pandemic?I think it’s all of the above. Every single film I make about space exploration, I just find the science is so inspirational. People who are trying to answer these big questions, like where did we come from? How did this all begin? It’s just, I just … And those who have the ability, like yourself, to share in that, and do it in a way that’s not only clear for the audience to understand, but also where you can feel your enthusiasm for it.I always feel it’s a privilege to interview scientists who are doing this kind of work. And to walk away from an interview understanding things that I never understood before, asking questions I never asked before. It’s never boring. Of course, it can be very difficult, and it can be a struggle. I sit with NOVA and we work on these films, and we do a tremendous amount of research. We do a lot of brainstorming about how to present the story, so I’m not doing it on my own. I’m doing it with two executive producers and a wonderful co-producer editor. All of these missions usually have more than one country involved because they’re so big. And scientists always talk about how much they enjoy working with people from other countries and take great pride in the fact that they are solving really complicated engineering and scientific problems together. It’s a great example for everybody else that we can do this.Science in many ways is good medicine right now.Caleb Scharf is the director of astrobiology at Columbia University. His latest book is The Ascent of Information: Books, Bits, Genes, Machines, and Life’s Unending Algorithm.Lead image: Still from Looking for Life on Mars, a NOVA production by Terri Randall Productions for WGBH Boston in association with Arte France and NHK.Read More…

Read More