America’s Obsession With Self-Help

Books about an idealized American character often make for a

body of elusive, exasperating speculations, delivered either on the fly or from

a special-pleading pulpit of one sort or another. So there’s something

appealing about reversing the polarity of such inquiries, and pursuing the

fugitive American character through a series of allegedly representative books.

That’s the task literary journalist Jess McHugh has set herself in Americanon,

gathering a baker’s dozen of influential and top-selling books that have helped

shepherd our republic through the successive trials of mass democracy, industrialism, and modernity, along with various upheavals in private and domestic life. For McHugh, most canonical works in the American grain

follow a pretty straightforward template: They are nonfiction books of advice,

built around a conception of a “good American” that, in McHugh’s telling, always

works to promote a narrowly exclusive brand of nationalism and marginalizes

any expression of racial, gender, or class-bound difference as suspiciously

alien and morale-sapping. These representative studies “allow us to see how

we’ve arrived in a time when fact is up for debate and American identity is

more divided than ever,” McHugh writes. “These books grapple with questions

such as: What does it take to be an American? And who gets to decide?” Just as

important, McHugh argues, these American texts are typically documents of

abiding personal struggles; they tend to narrate, inadvertently or otherwise,

an author’s quest for perennial self-improvement projected onto the national stage.

The books these writers have handed down to us “are the result of personal and

national trauma, and the stories they wrote come out of survivorship.”McHugh launches her survey with a tandem of reference works: The Old Farmer’s Almanac, first published in 1792, and Daniel Webster’s

landmark school “speller” and his dictionary of American English, respectively

launched in 1783 and 1823. (This latter work, of course, has been regularly

revised and updated through its long subsequent publishing career.) The pairing

seems a fitting departure point for a New World social order steeped in the mindset

of Enlightenment empiricism, but as McHugh notes, each work bears the

idiosyncratic stamp of its creators and the ethos of the early American republic.The Almanac’s founding father, Robert C. Thomas, was a

prototypical son of Yankee soil, raised in rural Massachusetts, and an ardent

admirer of Galileo Galilei; he went to Boston to study math and science, and

there hatched the aim of assembling an almanac of useful knowledge—a hotly

competitive niche in the small-farming America of the eighteenth century. His

efforts blossomed into The Old Farmer’s Almanac,

which compiled a pragmatic body of farm-centric information, from weather

forecasts to cheese-making tips, alongside a body of more broadly civic-minded

fare, such as the names and salaries of key political leaders and breakdowns

of religious doctrines and holidays. The cumulative effect of the almanac’s

eclectic and folksy account of hewing a living from the soil of the New World

was to enshrine the central myth of early America—that the origins and

long-term viability of the American experiment rested on the image of “the

yeoman farmer as patriot and model citizen.”Thomas himself exemplified the storied virtues of the small

landholder, McHugh writes; among all the authors gathered here, he’s strikingly

trauma-free (apart from a near-deadly brush with smallpox when he first moved

to Boston) and conducted his personal life in consistent accordance with the

advice he peddled in the public sphere. He even served as a Massachusetts

selectmen, and attended a convention to amend the state constitution, in a

seeming bid to carry out the dictates of Almanac living to their fullest.

Indeed, he died while correcting proofs of the latest edition of his almanac, a

suitably empirical and unassuming passage into eternity.Webster’s pocket

dictionary of 1806 appears to mark the first introduction of the word immigrant into print usage—prior to that, all border crossers were simply

“migrants,” no different from citizens who pulled up stakes within their

countries of origin. Webster’s obsessive, orthographic brand of American

homiletics, meanwhile, already augured a profound shift in national identity,

McHugh suggests: The young New York schoolteacher who published the Blue

Back Speller in 1783 was already entertaining visions of America as a bona

fide New World empire, and spent a tour as a newspaper editor touting his high

Federalist vision of New World dominion. He became taken with the idea of a new

dictionary of American English around the time he experienced his conversion to

evangelical Christianity at the dawn of the Second Great Awakening. (His

newfound faith greatly complicated his etymological researches, since he became

obsessed with documenting the common root of all language prior to the literal

fall of the Tower of Babel.) In his preface to his 1828 dictionary, he

seamlessly fused his exceptionalist vision of empire with the certitude of the

saved. The citizens of the fledgling American nation had burst onto the global

scene with an abundance of cultural riches, Webster wrote: “They commenced with

civilization, with learning, with science, with constitutions of free

government, and with that best gift of God to man, the Christian religion … in some respects, they have no superiors;

and our language, within two centuries, will be spoken by more people in this

country, than any other nation on earth.”Webster’s distinctly missionary-cum-nationalist zeal may

seem an odd fit with the philological work of dictionary research, which seems

to have little in common with plans for world conquest—but for romantic

nationalists of Webster’s age, special pleading through language was what you

might call a native tongue. Yet, as McHugh observes, Webster’s pocket

dictionary of 1806 appears to mark the first introduction of the word immigrant into print usage—prior to that, all border crossers were simply

“migrants,” no different from citizens who pulled up stakes within their

countries of origin. By the time the full dictionary was published in 1828,

Webster had further defined “immigrate” as “to remove into a country for the

purpose of permanent residence,” thereby effacing the widespread practice of

seasonal migration across national borders. The battle lines for future high-nationalist culture wars were drawn.Of all the writers memorialized in Americanon,

Webster casts the longest shadow. He was a close collaborator with fellow

educator William McGuffey, who as an erratically schooled child in Ohio had in

turn acquired much of his passion for learning from Webster’s Blue Back Speller.

His McGuffey Readers would sell more

than 120 million copies. And like his New England mentor, McGuffey produced

popular works of instruction steeped in a militant evangelical ethos, which would define American identity for a whole new generation of American

common-school students and political leaders. (One McGuffey lesson in

consonants contained this didactic-yet-casual outburst: “He cannot tolerate a

papist.”)Catharine Beecher, a nineteenth-century daughter of American

evangelical royalty (and the sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, of Uncle Tom’s

Cabin fame), presented a powerful domestic variant on the high-nationalist

mission pioneered by Webster and McGuffey. In her home-and-hearth guidebook, A

Treatise on Domestic Economy, she exhorted

her homebound female readership to renounce “the customs of aristocratic lands”

and to enact “the true principles of democratic freedom and equality” in their

management of the household. In such evocations of “an idealized American

exceptionalism in which women were called to lead,” McHugh writes, Beecher

“looked to do for manners and home life what Webster did for spelling and

language.” Though she wrote of women taking charge, she was a die-hard foe of

women’s suffrage, echoing the common claim that women possessed far stronger

and more enduring cultural power within the terms of domestic confinement. Even the 1970s sex guru David Reuben, author of Everything

You Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), partook of a rage

for order and cultural homogeneity, McHugh argues. While he was not extolling a

“national project or ideal American” as Webster had, Reuben nonetheless was

dedicated to “shaping an understanding of ‘American’ that was predicated on

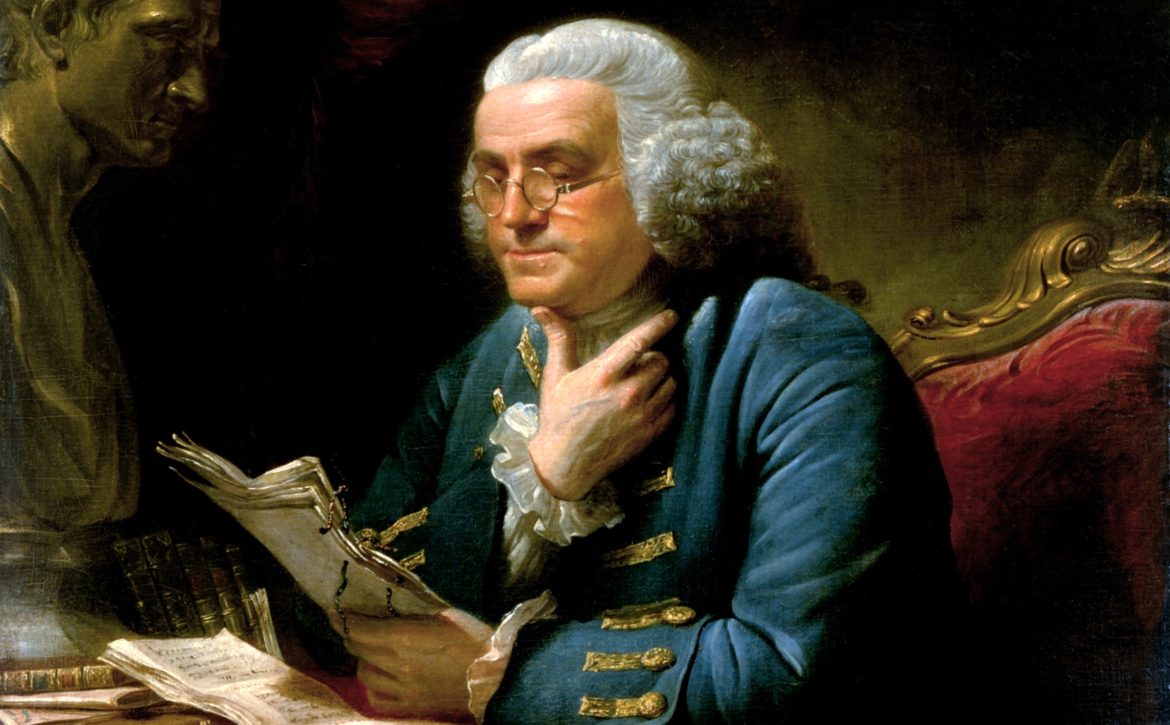

uniformity,” as he abjured LGBT and interracial sex in his guide.Only Benjamin Franklin, whose famed Autobiography was

the foundational text of the American self-improvement genre, rivals Webster’s

billing in Americanon. But

as an indifferent apostle of both organized religion and New World nationalism,

Franklin mostly figures in McHugh’s narrative as a genial progenitor of the

gospel of success—which proved an altogether more inclusive literary tradition

than Webster’s world-conquering linguistic nationalism.And that, in turn, points up a key limitation of McHugh’s

otherwise suggestive and imaginative survey. McHugh tries to argue throughout

the book that each of the works she examines tended to reinforce the same

process of cultural homogenization. Yet, while Franklin and Webster both wrote

out of an impulse for self-improvement, they are not, at the end of the day,

offering the same kind of advice.Franklin’s memoir (which as McHugh notes, departs

significantly from the actual record of the author’s life) presented an ideal

of the hyperorganized and singularly driven self as the great engine of

worldly endeavor and reward. He and his many later successor-prophets of

American self-help powerfully internalized the logic of market accumulation as

a foundational property of the self, and left a largely blasted social world in

their wake; failed, or failing, fellow Americans were to be left largely to

their own self-improving devices to work through their own worldly redemption. His

teachings on self-made success gained such powerful traction in American life and

thought precisely because they represented what Americans wanted to believe

about their own foreordained path to riches and renown. To use a profoundly

anachronistic term, they are aspirational, in the sense that John Steinbeck would

refer to the self-image of many American workers during the Great Depression as

“temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” For all of Benjamin Franklin’s single-minded focus on the habits of success, he was far from a straightforward apostle of

striving Americanism. Yet for all of Franklin’s single-minded focus on modeling

and extolling habits of success, he was far from a straightforward apostle of

striving Americanism. He was both a notorious libertine during his tenure as

American ambassador to France and an arch critic of the emerging tendency of

wealth to concentrate at the top of the social hierarchies of the New World.

When he presided over Pennsylvania’s constitutional convention in 1790, he

endorsed a failed resolution declaring that such accumulation “is dangerous to

the Rights, and destructive to the common Happiness, of Mankind”—and that each

state should therefore be empowered “by its Laws to discourage the Possession

of such Property.” Despite this, McHugh seems determined to turn Franklin

himself into a proto-Webster, quoting English professor Carla Mulford’s

judgment that “Franklin’s figure was used to obscure difference beneath a myth

of national unity.” It’s not that this estimation is wrong, per se—rather, it’s

that it explains everything and nothing. Yes, national myth-making tends to

obliterate difference in most historical settings—but tensions within such

myths produce significant changes over time. In the Jacksonian era, for

instance, McGuffey’s Readers are engaged in high-Protestant

myth-making, once more “demonstrating who is part of the ‘us’ and who is part of

the ‘them,’” while David Reuben’s sex manual published a century and half later

likewise “served as a violent standardizing tool, much like many of the other

books in this collection, penned by an author obsessed with ridding the country

of difference.”Clearly, though, David Reuben and William McGuffey aren’t

devoted to exactly the same process of cultural homogenization for its own

sake. And this is ultimately why Americanon, for all of its

energetically reported detail, ultimately adds up to considerably less than its

bestselling, culture-making parts. What’s more, if this disparate body of

advice manuals were in fact issuing the same rousing call to arms to the same

core white, imperial Protestant, that would be a striking demographic

continuity, running counter to all sorts of other national trends, that would

call for a far-ranging explanation of its own. Instead, the larger design of Americanon

produces a singular flattening effect, in which one fabricated cultural myth is

piled atop another, with no apparent resolution or egress on offer.Indeed, the book concludes with a bizarre extended

appreciation of the most storied recent self-help franchise on the American

scene, the business advice empire erected around Steven Covey’s monster 1989

bestseller, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Although Covey’s

tract pays no more attention to the harms of racism and sexism than the other

works McHugh examines, she finds its controlling agenda tempered by a

soft-focus emphasis on “principles,” “proactivity,” and “interdependence.” Such

qualities, she asserts, are in short supply in similar works of success

literature, introducing a critical element of vulnerability into the usual

morale-raising, virtue-forming proceedings: “In interdependence,” she writes, “there

was a recognition of individual limitations, even fallibility, in a way that

rarely happens in this type of literature.” This recognition was largely an attribute of Covey’s faith,

McHugh suggests. A devout Mormon, Covey maintained a regular meditation and

exercise regimen that suggest an effort to fuse the sensibility of

industrial-age time-and-motion studies with a sense of a deeper spiritual quest.First, he read

from the Bible while working out for at least thirty minutes on a stationary

bike. From there, it was fifteen minutes of vigorous laps in a swimming pool

and then fifteen minutes in the shallow end of the pool. After his exercise, he

retreated to his library to “pray with a listening spirit” and visualize his

entire day.McHugh insists that Covey’s work is “radical” for the way “Covey

expanded the tools for self-discovery, widening both the path to American

success and its definition.”In research for my own book on capitalism and American

Christianity, I read The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, and

suffice it to say, it struck me as neither especially groundbreaking nor

radical. In stressing the notion of “principles” and “paradigms,” it is indeed

in the mainstream of systems-driven business advice literature, pioneered by

thinkers such as corporation theorist Peter Drucker and business guru Clayton Christensen. And in hymning the interface of

inner-directed personal growth and business achievement, Covey built on the

sociological legacy of David Riesman, alongside the ravings of

corporate-excellence prophet Tom Peters.More than that, though, Covey’s use of business success as a

lens for understanding all personal development leaves no escape from work and

the logic of the market. When he provides anecdotes to illustrate self-improving

habits, he barely differentiates his career as a management consultant from his

life as a dad. The effect is more than a little jarring. The signal innovation

of Habit 2 (“Begin with the end in mind”) is to craft a “personal mission

statement” for the domestic hearth. Covey cites one such document from a

harried working mother, who vows:My home will be a

place where I and my family, friends, and guests find joy, comfort, peace, and

happiness. Still, I will seek to create a clean and orderly environment, yet

livable and comfortable.… I especially want to teach my children to love, to

learn, and to laugh—and to work and develop their unique talents.The notion of concocting a business-style mission statement

to instruct your children to laugh is a bit of strenuous overplanning that

would probably prompt even Ben Franklin to burst out into a torrent of bitter

guffaws.And there’s a still larger irony embedded in McHugh’s

prescription of Coveyism as the de facto cure for the crushing homogeneity of

the American canon: As any long-suffering employee conscripted into

cheerleading duty at company retreats, productivity-minded breakout sessions,

and the like can attest, the mantras of “interdependence,” proactivity, and

paradigm-blasting conceal a numbingly uniform managerial agenda of their own.

The idea is not so much to propel America’s overmanaged, relentlessly

surveilled workforces into bold new transports of creativity and inventiveness;

it is, rather, to coerce them into mimicking the exhausting, nonsignifying

jargon of authenticity that reigns in the C-suites and boardrooms of our

nation’s profoundly noninventive, counter-inclusive managerial classes. Unfortunately, though, that’s not a lesson that can be

boiled down into a self-help directive, a McGuffey reading exercise, or a

Webster’s dictionary entry. No, it can only be driven home via the

long-atrophied frontier American virtue of thinking for yourself.

Read More